The terms One China Policy (一中政策) and One China Principle (一中原則) are often used interchangeably. While both relate to Taiwan’s status, they carry different diplomatic meanings and commitments.

Confusing the two may be done intentionally or subconsciously. This can also be done deliberately in diplomatic contexts. Chinese officials have often deliberately conflated the two, claiming there is near universal acceptance of the One China Principle with over 180 countries and international organizations affirming their commitment. This is not only misleading, but also oversimplifies the complex realities of diplomacy with Beijing and Taipei.

What’s the difference?

The One China Principle asserts that Taiwan is part of China, and there is only one legitimate and sovereign state representing the whole of China, that being the PRC. Adherence to the One China Principle demands the exclusion of Taipei from international agreements and limiting Taiwan’s international legitimacy while reinforcing Beijing’s authority over the island.

In contrast, the One China Policy is a stance some countries take in navigating their relationships between Taiwan and China. Countries using this policy acknowledge the PRC’s claim over Taiwan but do not endorse it, which allows for strategic ambiguity. States can then engage with Taiwan unofficially while maintaining formal ties to Beijing.

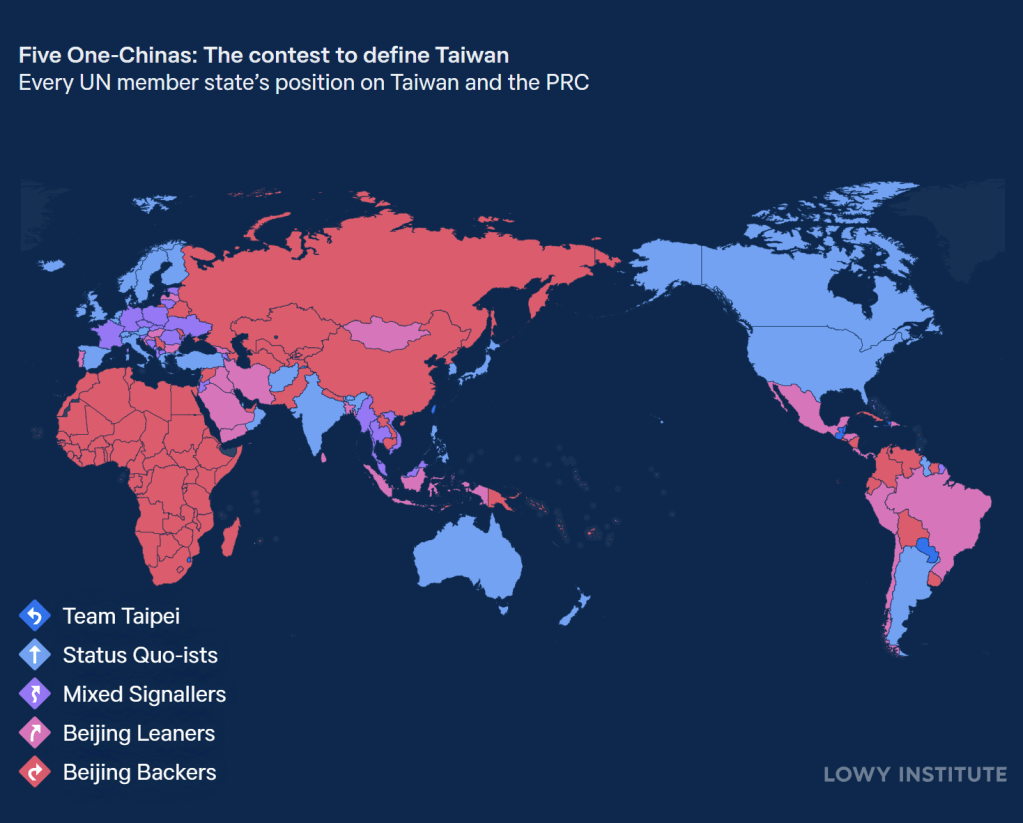

However, it’s not quite as simple as a country adopting one stance or the other. In January this year, the Lowy Institute put out a fantastic piece on this topic, dividing countries into five different categories: Team Taipei, Status Quo-ists, Mixed Signalers, Beijing Leaners, and Beijing Backers.

The Five Categories

Team Taipei recognize the Republic of China as the sole government of China and have little to no ties with the PRC. Meanwhile, Status Quo-ists recognize Beijing as the sole legal government of China but do not endorse the One China Principle, instead adopting their own One China policies to allow for strategic ambiguity. Mixed Signalers also recognize the PRC as the sole legal government of China and refrain from endorsing the One China Principle; however, they explicitly accept that Taiwan is under Chinese sovereignty, with less room for ambiguity.

Beijing Leaners endorse the One China Principle and recognize China’s sovereignty over the island. However, they stop short of explicitly supporting efforts to achieve “national reunification”, which is what Beijing Backers support. Beijing Backers support China’s reunification goal without insisting on a peaceful resolution.

While this is a helpful framework, the reality is far more fluid, with states shifting over time in response to political changes and shifting geopolitical dynamics. Countries usually fall between Team Taipei and Beijing Backers on a spectrum.

How did we get here?

After the Chinese Civil War, both the CCP and KMT claimed legitimate rule of a unified China. Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek agreed that there was only one China, so the two existed as existential threats to the other’s authority.

In the pre-normalization era, much of the world recognized the Republic of China as the legitimate Chinese government even after it retreated to Taiwan in 1949. Recognizing the KMT was a convenient way to oppose communism while still aligning with the One China narrative. However, things began to change in the 1970s, when diplomatic momentum swung towards Beijing.

The ROC was expelled from the United Nations in 1971, which dealt a devastating blow to the ROC’s international status. Eventually, the US and China officially normalized relations in 1979, the same year when diplomatic recognition of the ROC plummeted.

Where are we now?

While the PRC is internationally recognized as China’s government, Taiwan operates as a democracy with its own systems and identity separate from that of China.

Taiwan’s government today has an unwritten norm that the continued use of the ROC constitution serves as legal and political stability rather than a claim to represent all of China.

Taiwan builds deep partnerships through creative frameworks and shared interests rather than formal diplomacy. It also has Trade and Investment Framework Agreements (TIFAs), which provide the ability for Taiwan to have serious economic engagement without triggering political alarms that come with formal treaties. For instance, Taiwan’s TIFA with the U.S. dates back to 1994, giving both sides a formal channel to work on market access, intellectual property, and trade barriers, which aids Taiwan’s tech-driven economy that thrives on exports and innovation. The EU and Southeast Asian countries have similar arrangements with Taiwan.

In 2015, Taiwan launched the Global Cooperation and Training Framework, which lets Taiwan team up with international partners to offer training and share expertise on global issues like public health, disaster relief, and environmental protection. This creates a space where Taiwan can lead and contribute.

President Trump signed the Taiwan Travel Act in 2018, which gave U.S. officials the green light to visit Taiwan. This law paved the way for visits that would have been unthinkable a decade ago, such as President Tsai Ing-wen’s travel in the U.S. and Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in 2022.

Japan is one of Taiwan’s strongest unofficial allies. The two countries share history, economic ties, and political dialogue, which mostly flows through the Japan-Taiwan Parliamentary Friendship League. Former Japanese prime ministers and high-level officials have publicly expressed support for Taiwan — something few other countries dare to do. Taiwan also relies heavily on Japanese raw materials for its semiconductor chip making industry.

While the EU officially follows the One-China Policy, it still actively supports Taiwan’s international participation, especially in global organizations. In 2021, Taiwan scored participation in Horizon Europe, the EU’s flagship research and innovation program.

Many ASEAN countries host Taiwan’s de facto embassies — called representative offices — that operate a lot like real embassies. Some even grant diplomats tax breaks, diplomatic plates, and airport privileges. These aren’t small gestures; they’re subtle signs of respect and recognition. Countries like the Philippines and Singapore — which don’t share a border with China and are closer to the U.S. — give Taiwan’s offices the most freedom. Meanwhile, Cambodia and Laos, which rely heavily on Beijing, keep Taiwan at arm’s length.

The gray space in Southeast Asia has opened the door for the New Southbound Policy in 2016, which focuses on deepening ties with South and Southeast Asia through cultural exchange.

Only three Pacific nations still officially recognize Taiwan: Palau, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands. However, every recognition Taiwan holds gives it a louder voice on the world stage — and helps legitimize its claims to statehood. In return, Taiwan offers generous aid packages. Some scholars call this “sovereignty for rent” — where smaller nations trade diplomatic recognition for much-needed resources.

Where do we go from here?

The most common perspective of Taiwanese citizens, according to surveys by the Election Study Center of NCCU in Taipei since 1994, is to maintain the status quo indefinitely. However, while the majority of the population wants to maintain the status quo and persevere with the current state of affairs, there is a growing part of the population that wants to move towards independence.

Even without diplomatic recognition, Taiwan is building relevance. Through trade frameworks, training platforms, strategic laws, and innovation partnerships, it’s finding ways to plug into global systems without challenging the One-China framework head-on.

Instead of fighting for formal recognition it’s unlikely to win, Taiwan has mastered a different skill—showing up under different names, in the places that matter.

Taiwan has a couple of organizations to keep it connected to the international community. For instance, the Taiwan International Cooperation and Development Fund focuses on improving education, fighting poverty, and boosting healthcare in developing countries. Through this kind of aid, Taiwan is building lasting goodwill and quietly strengthening its diplomatic ties.

Another organization is the Taiwan External Trade Development Council, which works to promote Taiwan’s exports and connect its businesses with the world. It helps Taiwanese firms access international markets even in places where formal diplomatic channels don’t exist.

Lastly, the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy supports human rights movements, democratic development, and civil liberties — especially in regions under authoritarian rule. It offers funding, training, and global visibility for dissidents and reformers.

It is clear that there is a deep divide within Taiwan over how it should maintain its democracy, especially since in the last presidential election, there was no one party that gained the majority vote.

For more, check out Episode 2 of Dire Straits: