Written by Liz Joho

Published July 16, 2025

Dubbed “Silicon Island,” Taiwan and its 23.4 million citizens have carved out a place on the global stage as a vibrant democracy and a powerhouse in semiconductor manufacturing, with chips alone making up around 15% of its GDP. But this economic strength masks a critical vulnerability: Taiwan, with its high population density, limited natural resources, and isolated position in the geopolitical landscape, imports over 90% of its energy. As an island with strained ties to Beijing and very little official participation in international energy frameworks, Taiwan’s dependence on foreign fuel makes it particularly exposed to supply shocks. In a region marked by rising tensions and uncertainty, energy security isn’t just an environmental or technical concern: it’s tied directly to questions of national resilience, economic sovereignty, and even defense. Against this backdrop, Taiwan’s current energy debate is more than a political choice, but rather a balancing act between long-term sustainability and short-term survival.

Additionally, the 2022 energy crisis, triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, further highlighted the vulnerabilities in global energy supply chains and exposed the risks of dependence on imported fossil fuels. This global shock provides an opportunity to consider the direction of energy policy. Should policymakers use this moment to accelerate the green energy transition, as requested by overseas tech companies? Are renewables Taiwan’s only path forward to establish both robust energy security and fair energy sovereignty?

Firstly, understanding Taiwan’s energy debate requires first understanding the necessity for energy sovereignty and energy security. The latter is defined by the International Energy Agency (IEA) as “uninterrupted availability of energy source at an affordable price“. Recently, the importance of energy sovereignty has also been emphasized. Energy security’s definition varies depending on whether the country is an exporter or importer of energy; in the case of Taiwan, which depends on imports, securing supply chains significantly reduces this dependence. On the other hand, energy sovereignty implies communities’ and citizens’ right to self-determine their system and source of energy. This is particularly important as communities are those who suffer the potential negative externalities of energy infrastructure. Energy sovereignty empowers communities to control “the myriad environmental, economic and psychosocial externalities associated with energy production and transportation”. Examples of negative externalities include what psychologists call Wind Turbine Syndrome, where communities living near wind and solar farms suffer psychological distress due to close proximity. Hence, policymakers have been using opt-in subsidized programs to encourage and respect energy sovereignty. The Executive Yuan (the executive branch of the Taiwanese government) in December 2024 voted in a Residential Rooftop Solar Energy Installation Acceleration Plan, granting subsidies to homeowners and businesses to install rooftop solar PV. Opt-in users would be granted subsidies of up to NT$300,000 (US$9,229), funded by the Ministry of Economic Affairs.

Renewable Energy Feasibility:

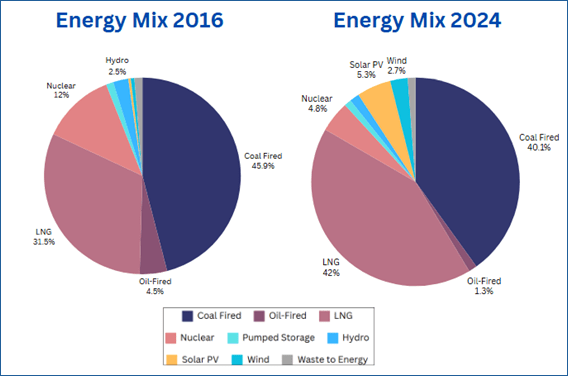

In addition to these challenges concerning dependence on exported energy, Taiwan also faces significant demand for green energy to feed its tech manufacturing sector. Nvidia, an American multinational technology manufacturing corporation, has requested 10 billion kWh of green electricity to consider setting up headquarters on the island. While the current administration has claimed it will be capable of delivering 55 billion kWh by 2026, most experts remain skeptical due to previously unmet green and renewable energy goals. Since 2016, the country has consistently underperformed on solar and wind energy targets. Tsai Ing-Wen, the previous Taiwanese president who came to power in 2016, had promised that 20% of the energy mix would come from renewables by 2025; however, the deadline was pushed to 2026 as goals were not met. Energy sovereignty and national security are inseparable, and ensuring the former while trying to meet the net-zero target by 2050 has proven challenging but pressing, especially in a context where the Taiwanese population has weakening faith in the country’s defense capability.

A shift toward renewables is often cited as a key solution to energy security. Decarbonization and reducing fossil fuel dependence can indeed limit geopolitical exposure; however, if this transition is too sudden and not carefully managed by governments, it can lead to market concentration as fossil fuel actors exit the market. Fewer players can increase dependency challenges and slow the diversification of energy sources. Expanding renewable capacity and diversifying supply can mitigate reliance on imports and intermittent energy, but this requires a gradual, controlled reduction of fossil fuels to prevent sudden supply shocks and price surges. Renewable energy also brings certain challenges; in some contexts, it can increase price volatility and affect affordability. These challenges, however, can be addressed through regulatory frameworks and Feed-in Tariff policies, as demonstrated in Germany’s high share of renewables in its energy mix.

Taiwan presents a unique advantage in renewable energy potential. It receives a high number of sun hours, making it well-suited for solar development. The government has recognized this and has been actively encouraging solar adoption through subsidy programs and incentive plans, as previously mentioned. In addition, its volcanic activity and hot springs offer strong prospects for geothermal energy. However, much of this geothermal potential is located within Indigenous territories or protected national parks, where strict environmental regulations limit exploration and development. Unlocking these resources would require changes to existing environmental policies—a politically and socially sensitive issue. So while Taiwan has the natural conditions to expand renewables, regulatory and land-use challenges remain key barriers that complicate implementation.

Balancing Risk and Security: Taiwan’s Nuclear Stance

As Taiwan struggles to meet its renewable energy targets, the debate around nuclear power has resurfaced; raising questions about how to balance risk, reliability, and emissions. The last few years have put nuclear energy back on the international stage due to its output stability, cost-effectiveness, and comparatively low carbon footprint. The European Union’s (EU) parliament voted on July 6, 2022 to block an amendment in the Sustainable Finance Taxonomy, paving the way for nuclear to be recognized as a “transitional” and low-carbon “green” energy source. By doing so, the EU has confirmed international trends and put back into the spotlight the question of nuclear energy, taking into account safety, waste management, and societal consensus.

Nevertheless, phasing out nuclear energy has been a key agenda of the current ruling party DPP as they desire to make Taiwan a nuclear-free country; however, opposition has been strong as they’ve at the same time failed to meet net-zero goals of 2025. On May 17 of this year, the last operating nuclear reactor, No. 2 reactor of the Maanshan Nuclear Power Plant in Pingtung County, was disconnected from the national power grid. The No. 2 reactor was generating less than 3% of the country’s electricity, and government officials have assured that alternative energy sources will be able to compensate for its shutdown. Local Pingtung government official Chang Yi (張怡), president of the country’s Environmental Protection Alliance, assured that the site will now welcome solar panels.

With Taiwan’s current electricity consumption exceeding available supply under the government’s ongoing denuclearization plans, the opposition party, the Chinese Nationalist Party Kuomintang (KMT), has voiced strong concerns about the risk of energy insecurity and potential blackouts. But their stance is not only political; it’s also deeply historical. Back in the 1970s, when the KMT was the ruling party, they authorized the construction of Taiwan’s first nuclear power plants. By the 1980s, three plants with six reactors were operational, and nuclear energy accounted for nearly 50% of the country’s electricity mix. Although the KMT acknowledges the inherent risks and limitations of nuclear power, it continues to argue that energy security must take precedence, especially in the context of growing regional tensions and national defense needs. Following the closing of Maanshan Nuclear Power Plant, KMT legislator Ko Ju-chun (葛如鈞) stated, “Nuclear power is not the most perfect way to generate electricity, but it is an option that should not be eliminated when we are developing technology, defense, and strengthening national security”.

Despite this perspective, social consensus on nuclear power remains elusive. Many Taiwanese citizens continue to express deep concerns about nuclear safety and the risk of accidents as the island is prone to natural disasters. The 2011 Fukushima Dai-ichi disaster in Japan, triggered by an earthquake and resulting in a level 7 meltdown on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, remains a powerful cautionary tale. Furthermore, past non-transparent government handling of nuclear waste storage has undermined public trust. Since the 1982, the government began storing low-level nuclear waste on Orchid Island (Lanyu, 蘭嶼), home to the Indigenous Tao people, without fully informing them of its true purpose. Residents were told the facility was a fish canner. Fearing history might repeat itself, especially after nuclear accidents in neighboring Japan, and frustrated by past government non-transparency, many in Taiwan remain strongly opposed to nuclear energy. These concerns have fueled persistent public resistance, complicating any efforts to reverse the nuclear phase-out policy.

Unlocking Hydrogen’s Role in Taiwan’s Clean Energy Transition

While nuclear remains polarizing, hydrogen has emerged as a less controversial but still technically demanding energy solution. Hydrogen fuel generates electricity through the combination of hydrogen and oxygen. This electricity is often dubbed a clean energy source; however, not all types of hydrogen are “clean” or zero emissions. Grey and blue hydrogen are both produced through the burning of fossil fuels, but blue hydrogen includes a storage dimension in its utility, making it low-carbon but not carbon-free. Green hydrogen, produced through renewable electricity via electrolysis of water, has zero emissions and can therefore offer Taiwan diversified energy sector possibilities, and the government The 2050 Net Zero plan aims to increase its share from 9% to 12%.

Beyond its environmental potential, hydrogen also stands out for its functional advantages, it presents a clean energy production possibility: it offers a certain stability in generation and allows for extended-period storage, especially when compared to its renewable counterparts, which face intermittency and storage challenges. However, the costs of infrastructure, production, and storage remain high. Hydrogen requires high-pressure, cryogenic tanks for storage and has relatively low energy density compared to other forms of energy. The industry therefore requires substantial funding for R&Ds.

Currently, Taiwan lags behind regional partners such as Japan and South Korea in terms of innovation in the sector. According to David Lin, head of the Power, Utilities, and Renewable team at Deloitte, hydrogen has tremendous potential as an energy carrier on the island; however, Taiwan currently lacks not only the necessary infrastructure but also sufficient renewable energy capacity. Taiwan’s high population density and limited geographical space for infrastructure often prove challenging for energy sources that require vast infrastructure, such as hydrogen and liquefied natural gas (LNG). Lin emphasizes the necessity for Taiwan to join other countries in their multi-billion-dollar funding plans to avoid falling behind in the global race and missing economic opportunities, especially in the context of green tech innovation among regional rivals. He stresses the importance of national policy concerning hydrogen energy, including carbon contracts, public and private incentives, and nationwide investments.

Charting a Path to Energy Resilience: Policy Recommendations for Taiwan

At the beginning of this year, the Taiwan Center for Security Studies hosted the 2025 Regional Security Tabletop Exercise (TTX), where a blockade scenario following Donald Trump’s election and the worsening of US-China tensions was simulated. In this exercise, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA), under the pretense of maritime inspections, targeted coal transports and LNG vessels to erode societal resilience and public morale, plunging Taiwan into a state of intense energy vulnerability. We found that Taiwan’s power grid would likely be the first to suffer due to geographical constraints, its current one-way power system, and dependence on imported fossil fuels. Even during peacetime, Taiwan faces disruptions in its supply chains due to typhoons and other natural events.

To address these risks, shifting toward bidirectional energy transfer could improve grid resilience by balancing supply during periods of high demand. Diversifying energy sources and investing in short-term measures such as LNG storage are also critical. Finally, decentralizing energy production and reducing reliance on the main grid through microgrids will be essential to strengthen Taiwan’s energy security.

Short-term solutions include improving energy storage, diversifying energy sources, and investing in LNG storage, though LNG is not a permanent fix. Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) present a flexible nuclear option but face regulatory challenges. Microgrids and decentralized systems can reduce grid dependency, but strong government support is needed.

Taiwan also needs a clearer nuclear policy to avoid delays in crucial decisions on plant extensions, as international trends show renewed interest in nuclear power. Delays could lead to energy shortages. However, extending nuclear operations introduces security risks amid rising regional tensions. The 2022–2024 period highlighted vulnerabilities with multiple blackouts caused by LNG terminal and plant safety system failures. In response, Taipower accelerated grid reinforcement efforts under a presidential directive. Proposed strategies include asset revitalization, flexible pricing, improved fuel procurement, and converting decommissioned plants into reserve facilities for wartime readiness.

Balancing energy security with decarbonization goals will involve trade-offs. While Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) is costly, Taiwan may still need a baseline of thermal power plants for grid stability. Restarting nuclear power remains one of the most viable paths to meet energy needs by 2029, requiring investment in plant upgrades to extend their operational lifespan.

The March 2025 TTX projected that Taiwan’s energy risk index could reach 0.99 by 2029, signaling an emergency. Experts recommend restarting nuclear plants and adopting dry storage for waste, alongside offshore or international disposal as longer-term options. Policy reform should also address inefficiencies in the Feed-in Tariff system and support market-based pricing, demand-side management, and smart grid technologies to strengthen resilience and transparency.

Comparing Regional Energy Strategies

In considering the future of Taiwan’s energy security, the experiences of South Korea and Japan offer valuable lessons. South Korea, like Taiwan, is an industrial democracy that relies heavily on imported energy and whose major energy companies are state-owned. It was also the first East Asian country to announce a state-led Green New Deal, aiming to balance sustainability with job creation while targeting carbon neutrality by 2050. The plan focuses on investing in renewables, green infrastructure, and the industrial sector as part of a long-term energy transition. Given these parallels, it will be interesting to observe the progress and potential feasibility of a Taiwanese version of such a national project, especially if early steps lead to positive outcomes. Japan, which faces similar risks from natural disasters, chose a different direction after the 2011 Fukushima disaster. While Taiwan decided to phase out nuclear power, Japan restarted its reactors to reduce LNG dependence, maintain energy stability and economic prosperity. The two approaches show that there’s no single answer to the energy transition.

Both of these contrasting strategies show that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. For Taiwan, the challenge is balancing its phase-out policy with the public distrust of nuclear power and its continued reliance on imported fossil fuels.

Whether Taiwan can build a stable, sustainable, and affordable system around renewables, hydrogen, or other alternatives remains uncertain, but the outcome could shape how other energy-vulnerable democracies approach the same problem.