TCSS Security Commentaries #036

we now know australia’s military requires a makeover to respond to the evolving strategic circumstances, but its key aquisition could be holding it back.

Ethan Pooley, intern, TCSS.

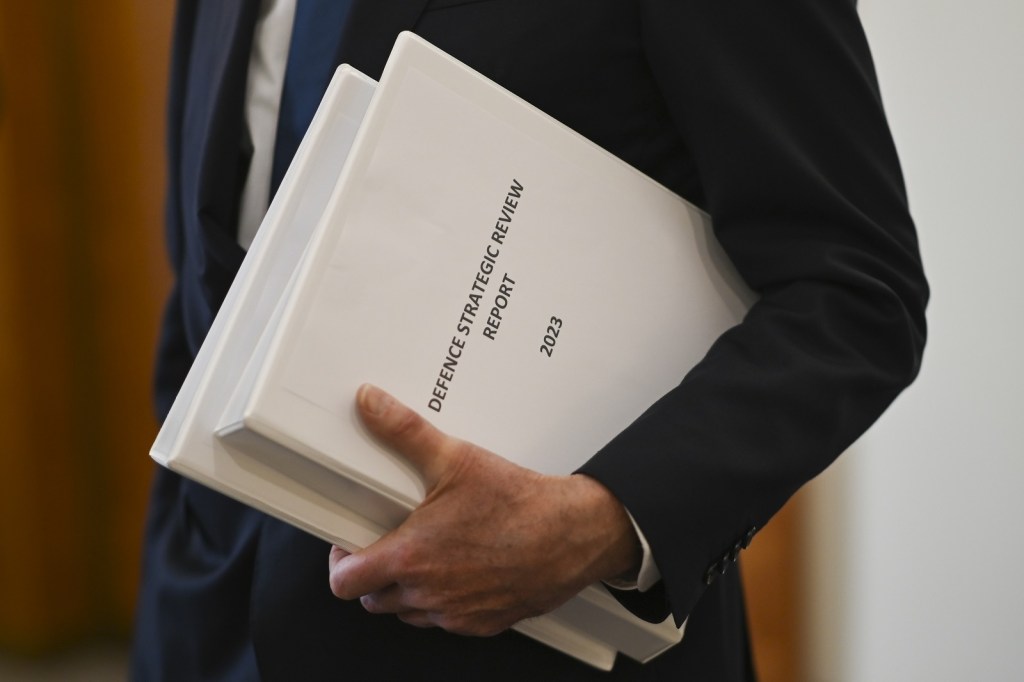

Action on the sweeping recommendations made in Australia’s Defence Strategic Review (DSR) – released to the public in April 2023 – is underway. This has been spearheaded by a change to the force posture of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) itself. This change will see the ADF transition away from the old doctrine of ‘Defence of Australia’ – which saw the ADF primarily concerned with Australia’s immediate territory – to ‘National Defence’ – which is intended to equip the ADF with the capability to protect Australia’s interests in its region (which, according to the report, covers the area from the ‘north-eastern Indian Ocean across to maritime Southeast Asia’). This will see the ADF shift from spreading its resources – human, financial and hardware – evenly across its various branches – a strategy appropriate for a time in which America was the uncontested military power in the region – to focussing these resources ‘much more’ in a way that enables it to implement a strategy of ‘deterrence by denial’. Going further than ‘deterrence by punishment’ – which involves being able to inflict enough damage to an aggressor that forces a change to their calculation – the strategy of denial will require the ADF to have the capacity to outright prevent aggressors from harming Australian interests.

This substantial change underscores that Canberra’s perception of risk and insecurity, stemming from the geo-strategic competition that is under way in the so-called Indo-Pacific, has become structural. In the preceding decades, the ADF could afford to distribute its resources to maintain a ‘balanced force’. However, as the report discusses, the opaque nature in which the PRC has developed an advanced military has left Australia concerned about its strategic circumstances. Few can deny these assessments made by the review – the balance of power in both the Indo-Pacific and the South-Pacific has become unprecedentedly contested. In this context, it is only natural to see the structure of the ADF evolve with the times.

In addition to the change in force posture, other steps toward fulfilling the DSR’s recommendations have been made. This includes repurposing the budget for military hardware to prioritise the acquisition of long and medium range strike capabilities instead of land-based vehicles. Also, the army’s plan to relocate 800 troops to northern Australia by 2025 is in process.

Whilst a start, these developments can be considered ‘low hanging fruit’ as they have not required an increase to the overall defence budget. In fact, the government has decided to defer changing the rate of defence spending until, at the earliest, 2026. However, by that time, it is anticipated there will be even more demands for funding in the defence sector – stemming from both a naval fleet review and the DSR’s suggestion to beef up the stock pile of missiles through developing a domestic capacity to manufacture the weapons. Without clarity on how this will be paid for, a greater burden will be placed on future governments.

It is understandable why the Albanese government would be cautious about increasing the budget in the current economy which sees public debt in Australia at record levels and pressures to increase funding coming from all sectors of society. However, there is an elephant in room – the plan to acquire nuclear-powered submarines under an agreement with the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK) at a cost of… US$240 billion over the next 30-odd years. So, with a defence budget under pressure, the enormous cost will undoubtedly require trade-offs that could see funding for other necessary capabilities and industries left underdone.

This is not to say the submarines are necessarily a bad acquisition. The nuclear-power means there is no need to re-charge the batteries – ever – so it can stay submerged, travelling at full speed, for weeks. This is a distinct advantage as the conventionally powered submarines Australia currently operates must surface roughly every three days to re-charge (if travelling at maximum speed), increasing the risk of it being spotted. Therefore, with regard to the deterrence by denial strategy, nuclear-powered submarines are an effective capability.

However, including the high cost, another downfall for the submarine acquisition is its timeframe. The agreement sets out four phases that begins with Australian sailors gaining experience on rotating US and UK submarines in Australia, then Australia will purchase three ‘off the shelf’ submarines from the US in the ‘early’ 2030s, then, in the 2040s, Australia will receive five newly designed submarines – taking the fleet to a total of eight. However, this seems to be directly at odds with a key recommendation made by the DSR: that the ADF should acquire military hardware based on ‘minimum viable capability in the shortest duration of time’ in order to respond to ‘the most challenging circumstances (in the Indo-Pacific) for decades’.

Implementing the recommendations made in the DSR is an opportunity to transform the ADF’s force projection capacity so it is fit to respond to its changing region. Like most policies, however, what stands between a good idea and on the ground results is funding. The DSR is clear in its assessments of the region and how the ADF should respond. However, both the cost and the decades long time frame of the submarine project appear out of step with the changes that are identified as imperative. As such, whether the high cost of the nuclear-powered submarines come at the expense of acquiring other necessary capabilities will be something to watch.

Ethan Pooley is a New Colombo Plan scholar undertaking an internship the Taiwan Center of Security Studies.